Any layout is a melange of challenges large and small. A bunch of these have slunk incrementally forward of late, which is just as well since another exhibition outing is looming. Rewanui has featured here from time to time without really exploring the design in detail. The whole thing was (mostly, hopefully) thought out some time ago, but as track completion approached I’ve been re-examining operation. In this edition of the blog, I’ll look at some of the operational matters relating to the layout, how these are impacted by design and the way they relate to what I’m trying to achieve.

Any layout (should) reflect the goals and whims of the builder. Rewanui was always intended to be:

- An exhibition layout. I’m not much into running trains, so one or two outings a year would well and truly scratch that itch while also providing motivational deadlines.

- A showcase for the way I like to build models. 99% of the time I’m focussed on a particular project, but the layout hopefully brings them all together and provides context.

- A proving ground for various things like scale wheels, auto-coupling and all manner of ideas stolen, original and adapted. Always a bit nerve wracking as while I have more than my share of success, there’s always a measure of failure to keep one grounded.

As time has gone by I’ve also become more focussed on making it able to operate much like the real thing. In my experience it’s not unusual for layouts to be difficult or uninteresting to operate. There are many possible reasons for this. Probably foremost is that it’s not something that is considered very much until it’s too late, a trap I’ve previously stumbled into myself. For the NZR modeller the constraints of the chopper coupling make life difficult, typically leading to a choice between operation involving little coupling/uncoupling or substitution of couplers that look nothing like the real thing. I’ve spent quite a bit of time working through possible solutions to that. Fingers were crossed for a workable solution.

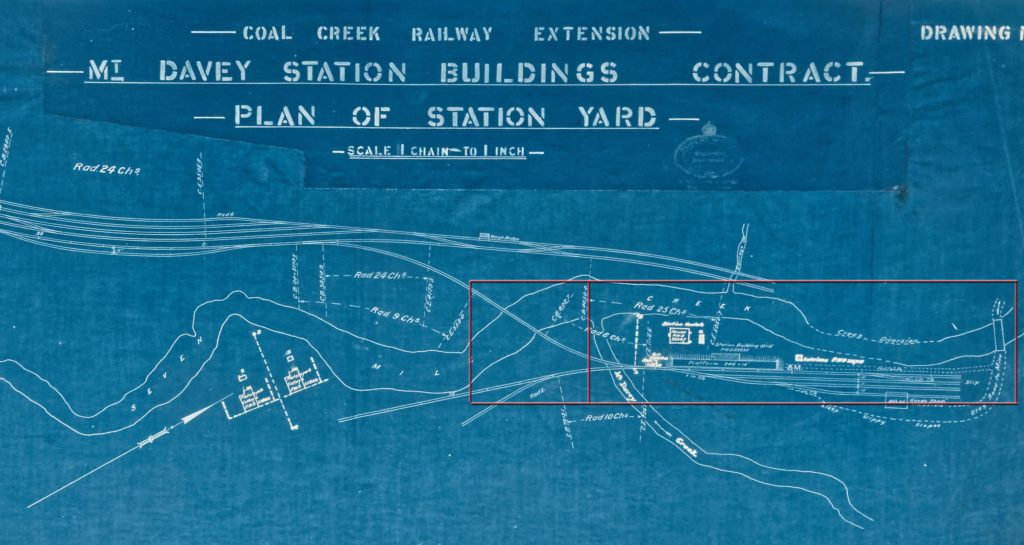

An early drawing of the station and environs. Note that at this juncture the name ‘Rewanui’ had apparently not been decided on and the line and station were the Coal creek extension and Mt Davy respectively. A detail worth knowing for the researcher as archival searches for ‘Rewanui’ turn up relatively little.

The drawing above has appeared in the blog before and illustrates the area modelled (within the red boxes) in the context of the wider infrastructure. The station sits within a narrow steep sided valley and, as can be seen in the drawing annotations, much of the yard site was cut and filled with the creek course diverted. It’s a very small station that can be modelled to scale. The working timetable lists the sidings having standing room for only 19, 15 and 12 18’6″ wagons.

In essence, the layout might be described as a minor branch line terminus, a subject explored ad nauseum in the UK modelling press over the years. In terms of the basic plan of the layout, this is entirely true other than swapping regenerating temperate rain forest for West Country pastoral. Small branch line termini are typically characterised by modest services, and models of them derive interest from shunting around what little traffic there is. It’s not as common an approach in NZR modelling as there were fewer termini, they tended to be sprawling (as land wasn’t an issue), and the frustration of chopper couplers is off putting.

At Rewanui however:

- There was no road access. Rail passenger services were therefore significant. The morning miner’s train was 7 cars carrying 250 or so workers. There were also uneconomic, but politically inspired, services (the ‘Semples’), to move small numbers of workers at night.

- The capacity of the mine sidings (off scene to my model) was huge compared to the modelled station (nearly 500 wagons). Goods traffic (almost exclusively coal) was far higher than the small station might suggest.

- The steep Fell incline to access the station placed severe limits on train sizes, and demanded novel working and unusual stock. At one point lavatories were removed from cars to reduce their tare weight, so things were obviously tight.

- Trains were short, but available loads were high, so trains were frequent. Sufficiently frequent that two locomotives in steam in the yard was a daily occurrence when there were colliers docked at Greymouth wharf. Trains were limited to 200t on the drawbar descending. Upwards of 1000t/day of coal could need moving (equivalent to over 1500t train weight).

- Down goods trains (up hill) are primarily empties that need to be transferred to the bin sidings, and up trains need to be assembled from full wagons. Visually this results in a lot of coming and going on the layout, even though movements between station yard and bin sidings are technically just movements within the linked yard.

- Coal was carried in a range of opens for on shipment by rail or various hoppers for on shipment by sea.

- Such inbound goods as there were seemed to be primarily pit props, sawn timber and tarped loads, together with explosives (typically carted in otherwise underutilised horseboxes).

- Short, slow trains were expectedly end of life roles for stock, so the vehicles are eclectic and interesting.

Operationally, therefore, the station was very busy with visually interesting workings. In other words a perfect modelling subject.

Layouts based on coal or mineral traffic typically have to deal with some sleight of hand to exchange empty wagons for loaded. In my design the bins and the wider world are both represented by a common fiddle yard. Empties travel from the fiddle yard up the incline to the station and over the back shunt back into the fiddle yard, while loaded stock does the reverse. Hopefully this looks like empties arriving and loads departing. There are a few exceptions to this that add a little additional interest. Rewanui coal was not ideal for locomotives, so loco coal was brought up the incline from elsewhere in a ‘coals to Newcastle’ style of working with a full open travelling up the incline. Conversely, there were private party bins along the incline that were loaded on Up (downhill) trains. As far as the layout goes this involves a train of empty opens travelling up to the station and then down without being loaded.

The layout is modelled as it was in 1940, and the stock is all appropriate to that. So strictly the layout should be operated according to the 1938 South Island working timetable. However the 1952 timetable is slightly more interesting and some of it’s unprinted vagaries were highlighted to me by the late Ian Coates. So I’ll probably take some liberties and run the 1952 timetable – albeit with everything else set in 1940. If this compromise ever troubles me I can revert to the 1938 timetable easily enough.

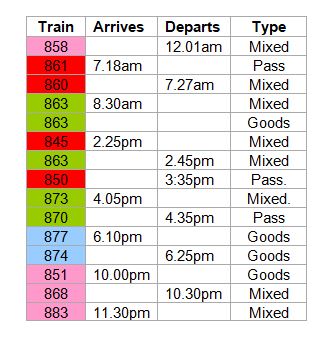

The timetable, based on Monday-Thursday from the 1952 SIWTT. The arrival of 863 and 845 results in two locomotives in the yard. This feature is the main driver for using the 1952 timetable.

The Rewanui timetable was not entirely straightforward with a number of workings ‘run as required’ or covered in footnotes. Given that traffic was highly dependent on the mine working and on shipping from the Greymouth port, flexibility to deal with traffic fluctuation was undoubtedly a must.

In the table above the colours represent crews/locos. On the real thing locos were not allocated to trains because they looked good, but due to haulage capacity, scheduling, crew shifts and so forth. Fortuitously this results in a number of different locos coming and going at Rewanui during a typical day. 861, the miner’s train, was always We hauled due to it’s weight. This locomotive and it’s crew would run the other services in red as well. When not running on the incline, the crew would have other rostered duties (in this case trains between Dunollie and Greymouth). 863 was able to make ‘up to 5’ return trips Dunollie-Rewanui, but these were not scheduled. If traffic was available these workings would fill the morning. 877 could also make an additional trip if required. According to Ian, 863 and 877 could also make party bin trips. These took longer, so a private party trip would take the place of two state mine trips in the day’s schedule.

All of this provides significantly more interest than simply shuttling a train back and forth. As far as the layout goes the plan is not to run to a clock, but to operate the services sequentially, jumping to the down service after a suitable pause after the preceding up service. Maybe with a clock slaved to the services rather than the other way around.

But will it all work as a model layout? Yes. As the video shows we’ve passed the point of proving all the basic concepts. There’s a lot of work still to do, but all the essential components work well. A hands free shunting layout with NZR couplers is entirely feasible. The pastel shade throttle needs a makeover and some refinement, but it all works really well.

The next task is to get some more stock up to standard to run some proper trains…